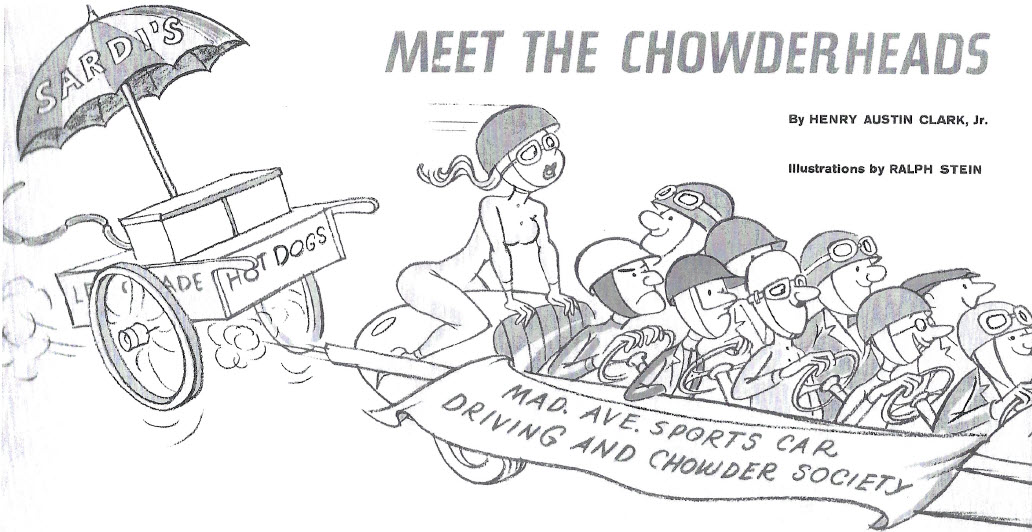

It is only natural to wonder why there should be such a rush for membership in an organization which the co-directors admit was founded for “no known reason,” had no accomplishments past or future, and which was unique in that it was “not mad at anybody.” Probably the answer is to be found in something a little deeper than a mutual interest in sports cars. Added to the uniformly excellent bill of fare provided by host Sardi (always carefully printed up on a special dated menu for the occasion), there is a varied program of entertainment provided for those who are able to partake of the typical two-hour Madison Avenue lunch “hour.”

Generally there is a film where two, usually on some phase of automotive competition and invariably so new that it is not been seen previously even by people close to the pulse of the industry. Frequently a new film receives its premiere at the chowder meeting, and on one occasion the gathering was treated to a preview of an hour television special by major network, complete except for commercials. At most meetings, there is a “Magazine of the Month” dis tributed free to the tables. New publications about cars, or general magazines with special automotive feature articles, are favored; usually the editor is found to be present as either a member or a guest, to be introduced and thanked by Art or King.

Generally there is a film where two, usually on some phase of automotive competition and invariably so new that it is not been seen previously even by people close to the pulse of the industry. Frequently a new film receives its premiere at the chowder meeting, and on one occasion the gathering was treated to a preview of an hour television special by major network, complete except for commercials. At most meetings, there is a “Magazine of the Month” dis tributed free to the tables. New publications about cars, or general magazines with special automotive feature articles, are favored; usually the editor is found to be present as either a member or a guest, to be introduced and thanked by Art or King.

As is the case with other clubs, an occasional wrench (U.S., metric, or Whitworth) finds its way into the machinery of entertainment. On one occasion the club projectionist, photographer Bob Grier, announced that the bulb had blown just before the showing of a film of the first Indianapolis 500 mile race, run at the brickyard in 1911. This being a silent film, the commentary was to be supplied by yours truly, H. A. Clark, Jr. Lacking the flickering image on the silver screen, we proceeded to give a lap-by-lap description of the race, including a specially vivid coverage of the rather blood-curdling accident in which a mechanic was run over by his own car after falling out. The audience gave no indication of having been short-changed on the program, and applauded mightily. This may give some indication of the serious outlook of a majority of the membership.

One of the most popular forms of program has been the slide lecture offered by one Mike Wormer, a news magazine executive. Using photos borrowed from the morgue (there is some question as to which one), Mike has produced lantern slides of highly dubious taste, to which he adds commentary linking well-known members of the group, such as sportsman Briggs Cunningham or writer-and-racer Denise McCluggage, with the slide being shown. After a half hour of a Wormer presentation the audience is almost too weak from rolling in the aisles to make it to the “Little Bar” for renewed strength.

Despite the avowed purposes of the Club being in the non-serious vein, its meetings have their substantial side. They are usually called to order by the “non-speaking” Director, King Moore, who may make a few announcements or introductions of visiting celebrities such as Stirling Moss, Oliver Gendebien, or Duane Carter. Eventually, Art Peck gets the microphone, and leads into the program. Perhaps Alec Ulmann will have a few dozen words to say in his famous unexpurgated style on the subject of his upcoming Sebring Twelve Hour Race; a candidate for office in the Sports Car Club may put in a bid for votes; or Bill France may give the inside dope on NASCAR affairs and racing. Frequently the triumvirate of Hewlett Tredwell, Ed Krom, and Lou Figari urge attendance by one and all at some sports car rumble at the “world’s fastest gravel pit,” Bridgehampton. These announcements do serve some purpose for those who wish to keep up with current motor sports events and are too lazy to read Art Peck’s column in “Competition Press”.

Despite the avowed purposes of the Club being in the non-serious vein, its meetings have their substantial side. They are usually called to order by the “non-speaking” Director, King Moore, who may make a few announcements or introductions of visiting celebrities such as Stirling Moss, Oliver Gendebien, or Duane Carter. Eventually, Art Peck gets the microphone, and leads into the program. Perhaps Alec Ulmann will have a few dozen words to say in his famous unexpurgated style on the subject of his upcoming Sebring Twelve Hour Race; a candidate for office in the Sports Car Club may put in a bid for votes; or Bill France may give the inside dope on NASCAR affairs and racing. Frequently the triumvirate of Hewlett Tredwell, Ed Krom, and Lou Figari urge attendance by one and all at some sports car rumble at the “world’s fastest gravel pit,” Bridgehampton. These announcements do serve some purpose for those who wish to keep up with current motor sports events and are too lazy to read Art Peck’s column in “Competition Press”.

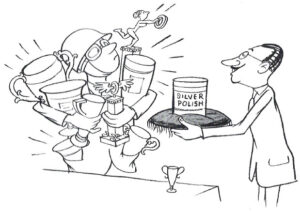

Once a year Frank Blunk takes advantage of a particularly full meeting to present the “New York Times” Awards for sports car competition. No other gathering gives such a wide audience for the announcement of these highly coveted prizes. Recently the Chowderheads gave an award of their own to member Phil Hill, America’s first World Champion Driver. It was a beautiful Atmos clock with an engraved plate stating the occasion and bearing tiny Chowder and Ferrari lapel badges. Only a few at this meeting remembered Phil’s first award from the M.A.S.C.D.C.S. It was a can of silver polish to be used for keeping his many other trophies dean. This first presentation was more in keeping with the spirit of the organization.

After a couple of years of indoor existence, some brave soul suggested a Chowder meeting off the sacred premises of Sardi’s. The first such experiment was in the form of a pool party at the home of a brave female member, Evie Lloyd, somewhere in the vastness of New Jersey. The party was a smashing success, and the high point occurred when the most formal member, Robbie Robinow (then of Mercedes-Benz), unintentionally entered the pool in full attire.

After a couple of years of indoor existence, some brave soul suggested a Chowder meeting off the sacred premises of Sardi’s. The first such experiment was in the form of a pool party at the home of a brave female member, Evie Lloyd, somewhere in the vastness of New Jersey. The party was a smashing success, and the high point occurred when the most formal member, Robbie Robinow (then of Mercedes-Benz), unintentionally entered the pool in full attire.

Following this delightful diversion it was only natural that other outdoor get-togethers would be scheduled. Two of these were in the form of week-end parties at Southampton, aided and abetted by several members with Eastern Long Island leanings. Difficulties in obtaining Saturday night accommodations were overcome by borrowing a vast unoccupied chateau on the beach, where the week-enders had a wonderful time roaming from wing to wing, partying until dawn.

Naturally these week-ends involved seeing some Chowderheads in sports cars for the first time, and Bridgehampton was the obvious place to find out whether or not they could drive them. Reluctant track officials permitted a Gymkhana on the straightaway of the 2.85 mile circuit, which was followed by a cocktail party at the track clubhouse on the hill. Such assorted machines as Peter Donald’s Kaiser-Darrin, a Leonard Potter Alfa-Romeo of early vintage, Tim Howkins’ 4½-litre Bentley, and Charlie Addams’ Alfa mingled with current-model Jags and Austin-Healeys.

The visitors were not permitted to leave the Hamptons without one of the traditional beach parties at the edge of the Atlantic with beer, hamburgers, corn boiled in sea water, and Jots of moonlight. Hardier souls went on to close up the Southampton headquarters of the Club at Herb McCarthy’s Bowden Square.

What is the future of the Chowder Society? Will it expand, coast along as is, or gradually pass on? Several chapters have been started in distant places such as Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles, Johannesburg, and, most recently, New Orleans. The first two have died out, the third operates occasionally, while the South African group has gone on steadily in a small way. The New Orleans chapter has not had time to prove itself on a long-range basis, but has fine prospects. As far as the original group is concerned, things have never been better. Most members feel that regardless of where the club goes from here it will be a fun trip.

For the first year, there were no dues, the cost of each advance-meeting notice being made up from a 25 cent markup on the luncheon. However, a need to control the membership list eventually led to the establishment of dues of $3.00. Both of the Directors, being friendly types, were in the habit of casually inviting more and more interested parties to join the group and would then promptly forget whom they had asked. As the room began to burst its seams, a limit of three hundred was placed on the membership, with the hope that not more than half of the faithful would show up at any given meeting. Invitations to join became more and more closely guarded.

For the first year, there were no dues, the cost of each advance-meeting notice being made up from a 25 cent markup on the luncheon. However, a need to control the membership list eventually led to the establishment of dues of $3.00. Both of the Directors, being friendly types, were in the habit of casually inviting more and more interested parties to join the group and would then promptly forget whom they had asked. As the room began to burst its seams, a limit of three hundred was placed on the membership, with the hope that not more than half of the faithful would show up at any given meeting. Invitations to join became more and more closely guarded.

Generally there is a film where two, usually on some phase of automotive competition and invariably so new that it is not been seen previously even by people close to the pulse of the industry. Frequently a new film receives its premiere at the chowder meeting, and on one occasion the gathering was treated to a preview of an hour television special by major network, complete except for commercials. At most meetings, there is a “Magazine of the Month” dis tributed free to the tables. New publications about cars, or general magazines with special automotive feature articles, are favored; usually the editor is found to be present as either a member or a guest, to be introduced and thanked by Art or King.

Generally there is a film where two, usually on some phase of automotive competition and invariably so new that it is not been seen previously even by people close to the pulse of the industry. Frequently a new film receives its premiere at the chowder meeting, and on one occasion the gathering was treated to a preview of an hour television special by major network, complete except for commercials. At most meetings, there is a “Magazine of the Month” dis tributed free to the tables. New publications about cars, or general magazines with special automotive feature articles, are favored; usually the editor is found to be present as either a member or a guest, to be introduced and thanked by Art or King. Despite the avowed purposes of the Club being in the non-serious vein, its meetings have their substantial side. They are usually called to order by the “non-speaking” Director, King Moore, who may make a few announcements or introductions of visiting celebrities such as Stirling Moss, Oliver Gendebien, or Duane Carter. Eventually, Art Peck gets the microphone, and leads into the program. Perhaps Alec Ulmann will have a few dozen words to say in his famous unexpurgated style on the subject of his upcoming Sebring Twelve Hour Race; a candidate for office in the Sports Car Club may put in a bid for votes; or Bill France may give the inside dope on NASCAR affairs and racing. Frequently the triumvirate of Hewlett Tredwell, Ed Krom, and Lou Figari urge attendance by one and all at some sports car rumble at the “world’s fastest gravel pit,” Bridgehampton. These announcements do serve some purpose for those who wish to keep up with current motor sports events and are too lazy to read Art Peck’s column in “Competition Press”.

Despite the avowed purposes of the Club being in the non-serious vein, its meetings have their substantial side. They are usually called to order by the “non-speaking” Director, King Moore, who may make a few announcements or introductions of visiting celebrities such as Stirling Moss, Oliver Gendebien, or Duane Carter. Eventually, Art Peck gets the microphone, and leads into the program. Perhaps Alec Ulmann will have a few dozen words to say in his famous unexpurgated style on the subject of his upcoming Sebring Twelve Hour Race; a candidate for office in the Sports Car Club may put in a bid for votes; or Bill France may give the inside dope on NASCAR affairs and racing. Frequently the triumvirate of Hewlett Tredwell, Ed Krom, and Lou Figari urge attendance by one and all at some sports car rumble at the “world’s fastest gravel pit,” Bridgehampton. These announcements do serve some purpose for those who wish to keep up with current motor sports events and are too lazy to read Art Peck’s column in “Competition Press”. After a couple of years of indoor existence, some brave soul suggested a Chowder meeting off the sacred premises of Sardi’s. The first such experiment was in the form of a pool party at the home of a brave female member, Evie Lloyd, somewhere in the vastness of New Jersey. The party was a smashing success, and the high point occurred when the most formal member, Robbie Robinow (then of Mercedes-Benz), unintentionally entered the pool in full attire.

After a couple of years of indoor existence, some brave soul suggested a Chowder meeting off the sacred premises of Sardi’s. The first such experiment was in the form of a pool party at the home of a brave female member, Evie Lloyd, somewhere in the vastness of New Jersey. The party was a smashing success, and the high point occurred when the most formal member, Robbie Robinow (then of Mercedes-Benz), unintentionally entered the pool in full attire.